Houston’s Blue and White Tiles: Signs of Progress

January 2026

Author: Brian P. Alcott

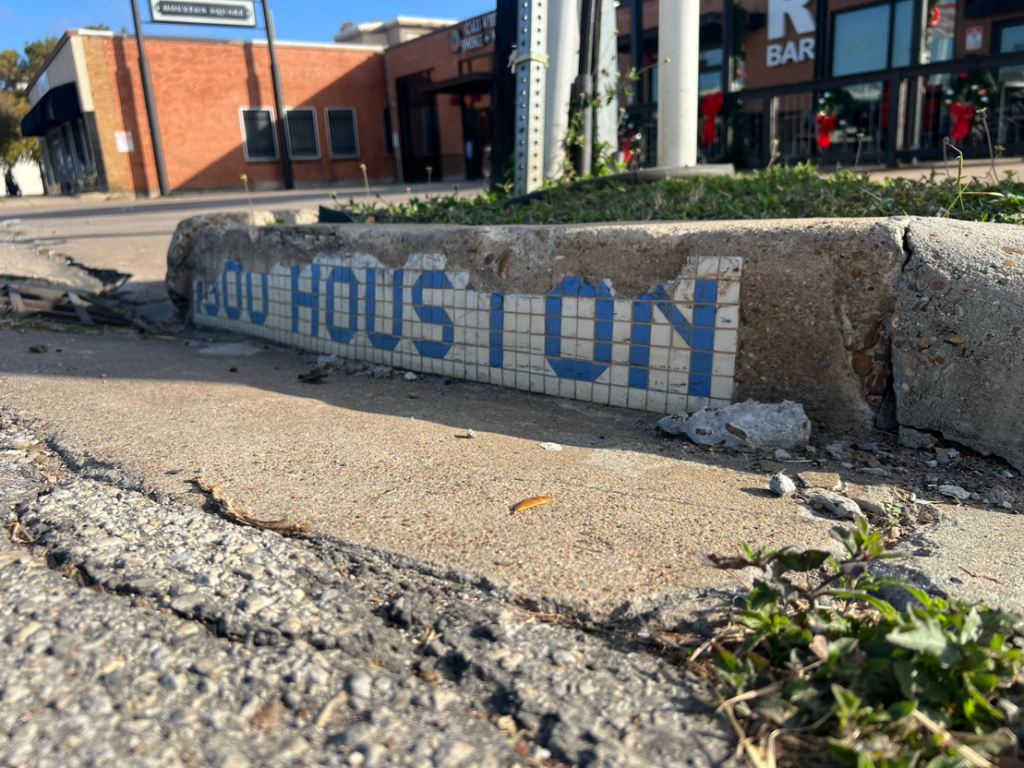

Houston’s blue and white curb tiles sit quietly in the streets, acting as understated beacons of the City’s history. Many Houstonians may live their entire lives without ever noticing these street markers, yet they remain an integral part of the City’s identity, providing a subtle sense of place and standing as reminders of a period of remarkable growth for the city of Houston.

Between 1890 and 1920, Houston’s population exploded, growing by more than 400%. In the 1890s, its streets were dominated by horse-drawn carriages, but automobiles soon began to appear. The Houston Daily Post reported only 80 automobiles in 1905, and by 1930, that number had surged to nearly 100,000. The city’s demand for new infrastructure to support such rapid growth was unprecedented and difficult to fully grasp.

Developing a city government and providing essential public services for Houston during this time was a slow and unpredictable process, shaped by trial and error under the relentless pressures of Houston’s rapid urban expansion. Even the seemingly straightforward task of creating usable streets, which served as the primary pathways for people, goods, and services, became a monumental challenge. As early as 1882, newspapers described Houston as “a huddle of houses arranged on unoccupied lines of mud.”

To sustain and support regional growth, Houston’s roadways needed to evolve quickly. The city experimented with a wide variety of materials for pavement. In the early 1880s, the city laid 15 blocks of gravel. By 1903, it boasted 26 miles of paved streets using not only gravel but also brick and asphalt, while experimenting with macadam and bois d’arc blocks, both of which could warrant their own ASCE articles.

One might assume that as the streets themselves matured, directional signage would develop in step. Yet this was not the case. Up to the early 1900s, street signs were among the least of the City’s concerns. That began to change as wayfinding frustrations started to grow among the residents of the expanding metropolis. Beginning around 1910, citizens began voicing their concerns. “Houston is known to be sadly deficient in the matter of street signs,” stated a civic leader, as reported by the Houston Post in May 1910. Later that year, Postmaster Seth B. Strong pleads that “The absence of street signs in this city is a matter of serious consideration.” Houston newspapers continued to be riddled with widespread discontent on the issue well into the early 1920s. But it wasn’t for lack of eNort on the City of Houston’s part. Supply chains, manufacturing, weatherproof materials, these were all things that simply didn’t exist at the time. The City did issue contracts for street signs to be built using the materials available: wood and paint.

However, one person’s wayfinding system can easily become another person’s irresistible target. In an era before Instagram, iPhones, or even television, boys were constantly seeking a quick thrill, anything to pass the time. And with streets covered in gravel and wooden targets springing up across town, mischievous young boys were in heaven.

In late 1910, a City contractor installing new signs grew increasingly frustrated, as every morning his crews arrived to find the previous day’s work completely destroyed. When the City finally got the vandalism under control, the quick-witted boys simply invented a new game. Late at night, they would slip out into the streets, quietly and strategically swapping signs around town. The next morning, they would sit back and watch as confused residents rushed to an address, only to find themselves completely lost.

Despite the City’s best efforts, it seemed that all hope for a reliable street-sign system was lost. That is, until our unlikely hero made its debut: Houston’s infamous blue and white curb tiles, quietly taking its place as the savior of wayfinding chaos.

The street-sign issue resurfaced in late 1915, again making headlines. City officials acknowledged the need for signs, yet admitted they had no solution for preventing “mischievous boys” from removing them. A December 5, 1915, Houston Chronicle article appears to be the first mention of the tiles reporting that in a meeting with City officials, it was mentioned that “the new sidewalks at corners, when built, be required to have the street name embedded with porcelain letters in the cement.”

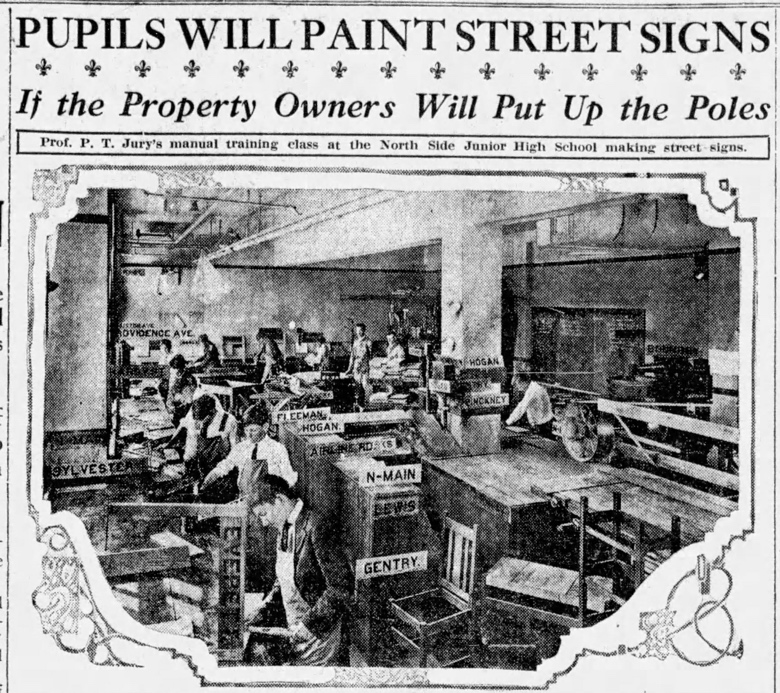

However, it would take years for the City to implement this solution. Between 1915 and 1922, Houston’s street sign saga continued to unfold. In the meantime, and perhaps in a twist of karmic coincidence, the City turned to an unexpected source: schoolchildren. In an effort to curb costs and, ironically, put some of those “mischievous boys” to productive use, officials enlisted students to help produce thousands of signs. In 1916, headlines declared, “Street Signs Will Be Made by 1,000 Fifth Grade Boys,” and by 1920

newspapers continued to report that “10,000 street signs were made by the students of the Manual Training Department of the City Schools.”

As schoolchildren continued making street signs over the years, the City slowly moved toward adopting the blue and white tiles as a long-term solution in classic municipal political fashion. In 1917, JC Hutcheson Jr. made street signs part of his mayoral campaign platform. After winning the election, he arranged for third-party utilities to install signs on their overhead wires. By late 1918, however, the mayor appeared to have forgotten the agreement entirely, and city officials were asking for the city detective to investigate the matter.

The issue resurfaced during Oscar Holcomb’s 1921 mayoral campaign. On April 2, 1922, Mayor Holcomb directed the city engineering department to mark all new street corners with street names in five-inch-high tile letters, carefully embedded into the curbs. As the Houston Chronicle reported, “He states that by placing the sign in the curbing, it will be difficult for the boys to remove it.” Later that year, on November 21, the City officially adopted two methods for installing street signs: curb inlays and hung signs. In doing so, Houston cemented its blue-and-white tiles into the city itself, creating enduring markers that would guide its residents for generations.

Although many still exist, Houston’s blue and white curb tiles have gradually vanished, replaced by the march of progress. As residents navigate a modern, diverse city while seeking to remember its past, interest in these tiles has grown. Yet no federal, state, or city protections apply to historic infrastructure located within public rights of way. Preservation, therefore, rests with the community. Houstonians, as well as residents of similar cities, must champion these modest but meaningful anchors that help us navigate where we are and remember where we came from. As folklorist Henry Glassie reminds us, “Buildings, streets, and public spaces are memory made concrete; destroy them, and you destroy part of yourself.”

Yet hope exists. Whether young Houstonians realize it or not, the blue and white tiles remain woven into the city’s present-day identity, not only in its streets but in its cultural expressions. Blue Tile Coffee along Washington Avenue reflects this connection. Though sleek and modern, its name and motif honor Houston’s past, creating a subtle but meaningful sense of place and belonging. It offers more than morning coffee. It fosters community and reminds future planners, engineers, architects, and all Houstonians that while a city is built from concrete, steel, and landscape, its soul is found in its history.